American Folk-Rock Neo-Renaissance Liturgical Modalism!?

This post is about a composer whose music I grew up with in the Lutheran Church, and recently revisited with fresh ears: Marty Haugen

Marty Haugen writes and plays a lot of music in the Lutheran Church. I will be focusing on his setting from 1990, “Now the Feast and Celebration”, which I grew up singing from grade school. The setting loosely follows a traditional Mass Ordinary, with additional pieces between readings, offertory, and communion. What I really want to focus on is his blending (in my view) of numerous writing styles, creating a 20th century setting grounded in the writing of much earlier time periods.

First, a brief breakdown of styles employed:

Psalm Tones: Traditional reciting tones, often employed in the singing of psalms or prayers. These appear across time periods since the 800s in various forms. In Haugen’s setting, they are employed in a traditional call-and-response, with or without ensemble accompaniment.

Modes: Scales such as Mixolydian and Aeolian, seen in church music as far back as Gregorian plainchant of the 800s, as well. Versions of these scales are also used in modern jazz and popular music, which the composer utilizes to bring the sounds of both time periods together.

Modal Interchange: Related chords are frequently spelled within the notes of a single scale. For example, in C major, chords are all spelled without sharps or flats. A modal interchange switches to a parallel mode, in this case C minor, where related chords would now contain the flats Eb, Ab, Bb. This is a very dramatic and emotionally charged way to write. It is most commonly employed in Jazz, and in the pop music of Stevie Wonder, but historical examples include the “Picardy 3rd”, which is said to arise in the Renaissance era.

Renaissance Dance: The meter of the title piece “Now the Feast…” is 6/8 and highly reminiscent of the Galliard, a widespread dance from the 1500s. In addition, the score indicates a woodwind ensemble in C (Flute, Oboe) and the addition of clarinet and bassoon is extremely effective. Although the music is not traditional to the time period, the affect is clearly similar.

American Folk-Rock: The composer is a singer-songwriter and guitar player. All of the works in this setting have optional acoustic guitar parts, and the composer’s own performances have a strong affect of 1960s-70s American popular music. This is intended, in the words of the composer, to aid listeners in “hearing their established texts and music with new ears”. This statement, to me, establishes the composer’s intent in blending style periods.

Now, an analysis of some music segments and how Haugen combines the above elements:

Kyrie: Aeolian setting of psalm tones. Generally a traditional minor sound, the frequent use of the flatted 7th scale degree in this mode gives it the “old church music” feeling. This is consistent with other short pieces in the setting. The ending, however, has the first example of modal interchange, utilizing the “Picardy 3rd” to shift from E minor to E major on the final chord. This is a structural segue as well, with the next piece in E major.

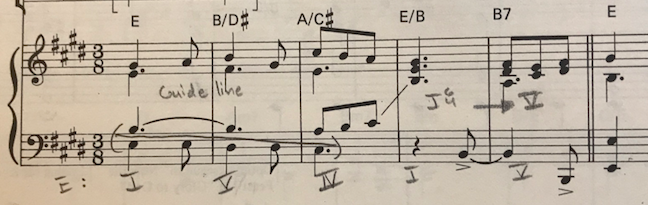

“Now the Feast and Celebration“: Title song. This is an alternate Gloria setting, replacing the traditional text with a more modern one as per the composer’s previously stated intention. There is a lot going on all at once in this piece. First, the Neo-Renaissance galliard dance feel is consistent throughout. Next, the bass lines are very smooth guide-tone lines, showing a pop/jazz influence in contrast to chorale/hymn settings. Finally, elements of other time periods arise in moments of text-painting or coloration.

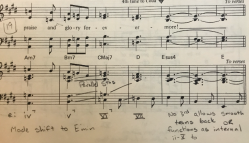

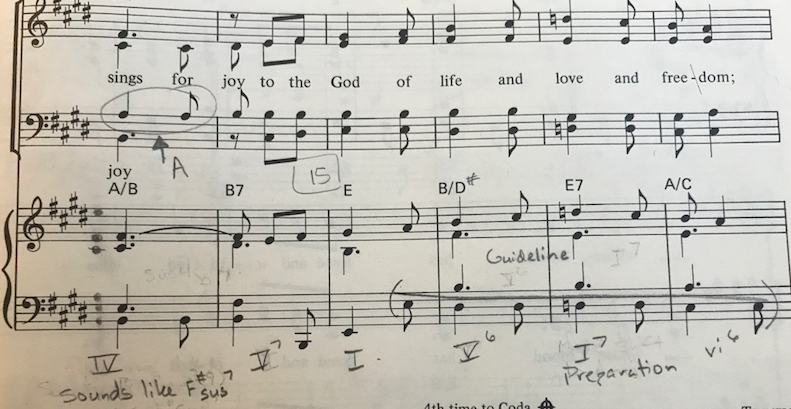

In the introduction, a smooth guide-tone line in the bass ends with a traditional I6/4-V motion, keeping the bass the same between the chords. In the following refrain this motion happens again, but is extended to a complicated pre-dominant motion labeled as [F#m to the slash-chord A/B to B7]. The function of this chord is a bit more complex, however, as the notes of the slash-chord are BEC#F#, which would be scale degrees 2-5-3-6 in the key of A, and makes very little sense, with only the choir tenors having the supposed root of A. I believe this chord is more accurately expressed as [F#min to F#sus7 to B7], which functions as an internal ii-V progression between the ACTUAL ii-V of [F#min to B7]. This takes us neatly back to the tonic of E.

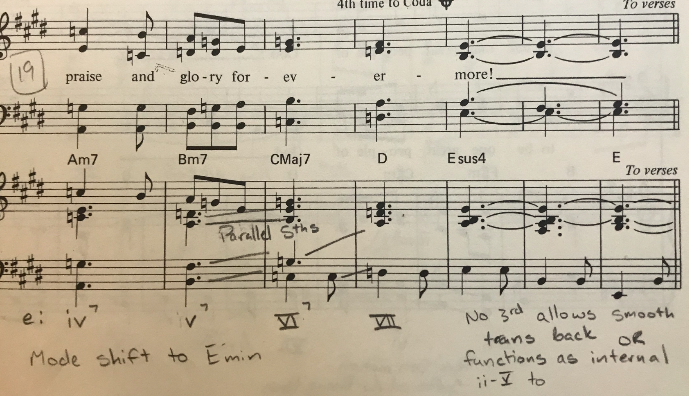

Now, Haugen employs some text painting. The phrase in m15 also begins as Emaj to B/D# (mismarked in the score as B/D). In m17, on the word “love”, there is an E7 chord using the flat 7 as in his Aeolian ‘Kyrie’ in preparation for the upcoming modal interchange. The interchange officially occurs in m19, rounding out the second half of this phrase in E Aeolian. This is the same modal interchange used by Stevie Wonder to color his most emotional lyrics, and several video analyses are available on the subject.

Haugen closes this genre-bending phrase with an early style period element followed by an open-ended jazz sonority. First, Haugen employs the deliberate use of parallel 5ths from m20-21, a stylistic mark of chant from before the year 1350. He then closes on an Esus4 chord, which has neither major nor minor tonality, leaving him free after each refrain to modulate to the verses in three different keys: C# minor, E Aeolian, and E Mixolydian.

There are many more examples of all the above compositional tools throughout this setting, but I’ll end here and allow you to explore on your own if you’re interested. The piece can be purchased at GIA publications in several formats. I used the Vocal/Keyboard/Guitar score for my analysis.